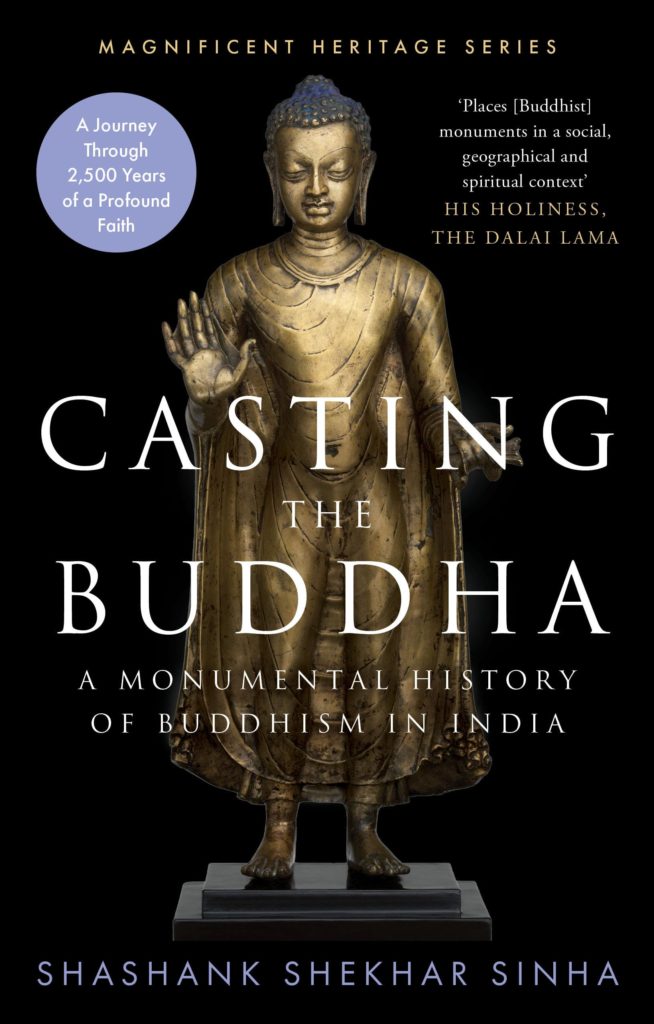

I picked up ‘Casting the Buddha‘, authored by Shashank Shekhar Sinha, immediately after a field trip to the Buddhist and other rock-cut monuments in and around Aurangabad. The trip had included, apart from well-known tourist magnets like Ajanta and Ellora, the awesome grandeur and raw power of less-known, and even lesser-visited, Buddhist sites like the unfinished Ghatotkacha Caves and the now-ruined Pitalkhora monastic establishment.

The Western Ghats have been worked by generations of artisans to create rock-cut sanctuaries and monasteries — from austere cells where monks once resided, to awe-inspiring chaitya halls for prayer. In other places too, covering virtually the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent, Buddhist monuments like stupas, temples and monasteries thrived for centuries, from at least the third century BCE. Why is it that this land is dotted with innumerable Buddhist monuments in various forms? What role did they play in the transmission of the Dhamma across the landscape of Bharata, and beyond?

Research on Buddhism, and Buddhist monuments in India has a long history, and yet information on these monuments is invariably scattered across numerous books on selected sites or monuments, lost in the voluminous literature on the subject. This is where Casting the Buddha makes a difference. Within the covers of one book, Shashank presents, in clear and lucid prose, the entire gamut of information with which even a rank beginner can grasp the origins and evolution of Buddhism in the land of its birth, and the role monuments played in the practice and propagation of the faith. This is not a book for the novice alone, though — even seasoned researchers can gain insights from the erudition of the author, as he even weaves in the latest information from current research.

Thus, we read not only about how Siddhartha, the Prince, renounces a royal career in his quest for enlightenment and founded the Sangha but also how humble temporary dwellings in the monsoon retreats of the otherwise itinerant Bhikkus became prototypes on which much of later architectural form in India was modelled. We learn not only about the practices of monastic Buddhism but also the religious and socio-economic milieu in which both the faith and its monuments were embedded in.

Although the primary focus of the book is the architectural vocabulary of the monuments, it also addresses what meanings these held for the contemporaneous people and communities in their surroundings, the interplay of religion and philosophy with architecture, and the role which various people like kings, artisans, traders, and the laity played in the construction and use of the monuments. The late infusion of tantric practices into the Vajrayana tradition is discussed, as well as the possible reasons contributing to the decline of the faith.

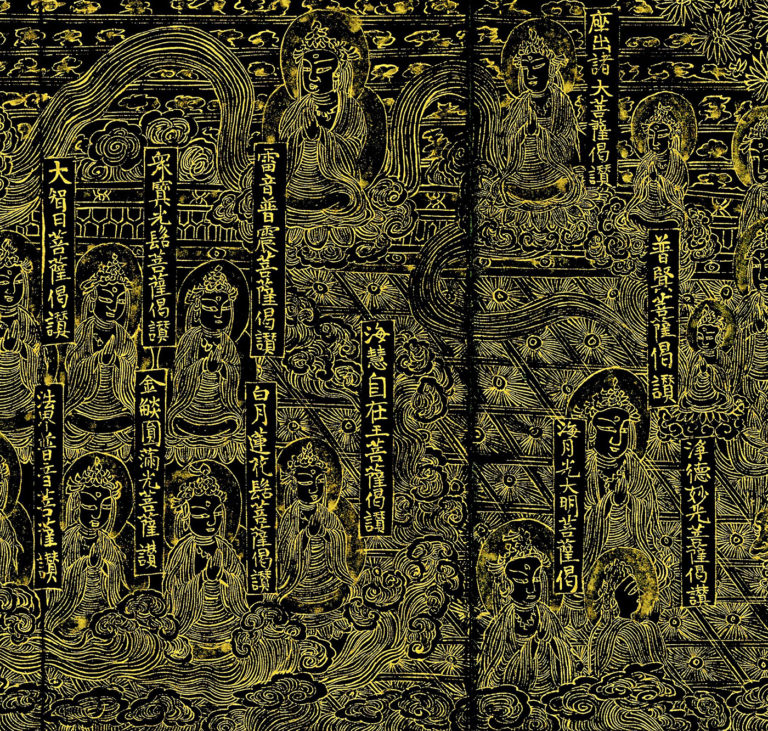

In five chapters, the first section deals with the founding of the Dhamma by the Buddha, and its progress in the following millennia, accumulating the trappings which came to characterise the faith — such as the cult of worshipping relics (of the Buddha and other spiritual leaders) in stupas, which became the foci of monastery complexes. The adoration of aniconic representations of the Buddha in the early tradition, which gives way to the worship of Buddha images with the advent of Mahayana is explained, as is the accommodation of regional cults and deities within the larger pantheon, such as the importance accorded to the Naga cult in Buddhist worship.

The second section discusses four monument complexes which have earned the UNESCO World Heritage tag — the Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya, the group of stupas and other monuments at Sanchi, the Ajanta rock-cut “cave” complex scooped out of a horseshoe-shaped scarp of basalt along a meander of the Waghora River and the ancient University complex at Nalanda.

The last section devotes two chapters to the “rediscovery” of Buddhism in the West and contemporary Buddhism today, including the Buddhist Circuit as a major attraction for international tourism. As I read these final chapters, I recalled my recent visit to the Ghatotkacha Caves, some 13 km to the west of the Ajanta Caves. My exploration of the large vihara there, patronised by Varahadeva — the same Vakataka Prime Minister who sponsored the magnificent Cave 16 at Ajanta, was interrupted by the arrival of a group of neo-Buddhists from Aurangabad. They paid their respects to the massive image of the Buddha carved at the rear of the sanctum and commenced chanting. For a few moments, despite the irreconcilable faults in the rock which must have led to the abandonment of centuries, despite the hundreds of bats and thousands of cockroaches which seem to have taken over the cave, this forgotten vihara reverberated with the spirit of the Dhamma, and I was transported to that bygone world.

And that is what readers of Casting the Buddha can expect from the book — an immersive experience in the life, and afterlife, of Buddhist monuments.

The reviewer is an Associate Professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.