In the Yangon River, a tiny island sanctuary is quietly defying Myanmar’s tourism boom. Yele Pagoda, perched on a reef near Thanlyin, has stood untouched by floods or fame for over 1,700 years — and locals intend to keep it that way.

Unlike the bustling Shwedagon Pagoda, which draws thousands daily and charges $8 entry, Yele welcomes fewer than 100 pilgrims each day. There are no bridges, no ticket booths, and no fixed ferry schedules. Access is by boat only, with monks deliberately maintaining unpredictability to deter casual tourists and preserve the site’s spiritual integrity.

Built in the 3rd century BC, the pagoda sits on a lateritic reef geologists call improbable. Monks attribute its survival to three ancient wishes, including one that promises blessings to those who protect it. That promise fuels the community’s resistance to mass tourism, including rejecting government proposals for pedestrian bridges.

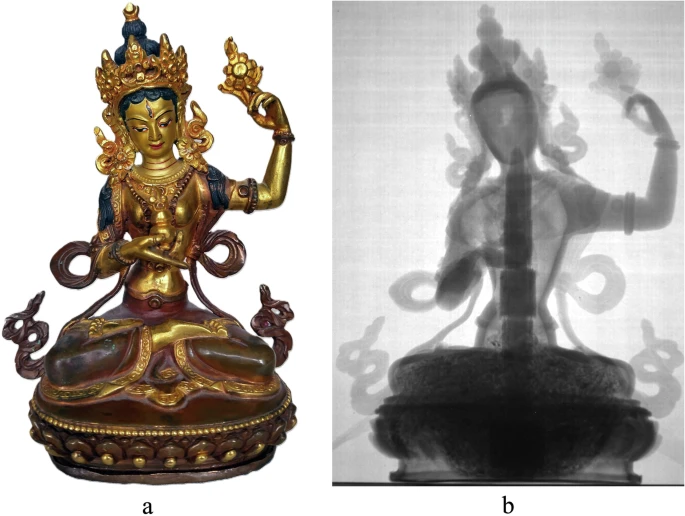

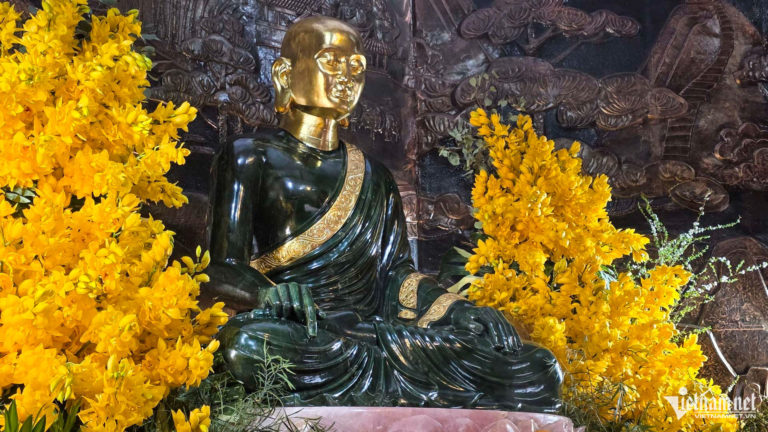

Inside the pagoda’s sanctum — open only during full moon ceremonies — monks guard what they claim are strands of Buddha’s hair, housed in gold reliquaries. Photography is gently discouraged, not by signs but by quiet redirection, preserving sacred moments from social media spectacle.

Yele operates on donations, not fees. A Thai grandmother’s 500 kyat offering recently led to an hour-long exchange with monks — a depth of interaction impossible at commercialised sites. Visitors can also feed giant catfish, believed to carry reincarnated souls, as part of Buddhist merit-making rituals.

Respect is key. Modest dress is required, and those arriving in shorts or tank tops are turned away. The dry season from November to February offers the best conditions, especially during the Thadingyut Festival when the island glows with candlelight.

For those willing to cross the water with reverence, Yele Pagoda offers more than a photo — it offers a glimpse into Myanmar’s living spiritual heritage. And for the locals who guard it, that silence is worth protecting.