A 17th‑century stone Buddha triad at Sinheungsa Temple in Yangsan, South Gyeongsang Province, has been preliminarily designated...

The British Museum has completed a major conservation project on its colossal Amitābha Buddha, returning one of...

Kelantan’s famed Sleeping Buddha statue has long been more than a religious landmark. Rising 41 metres in...

In the heart of Angkor’s Ta Prohm temple, the Hall of Dancers has emerged from decades of...

An exhibition tracing the rich history of Chinese carpet weaving has opened at the MITA Museum in...

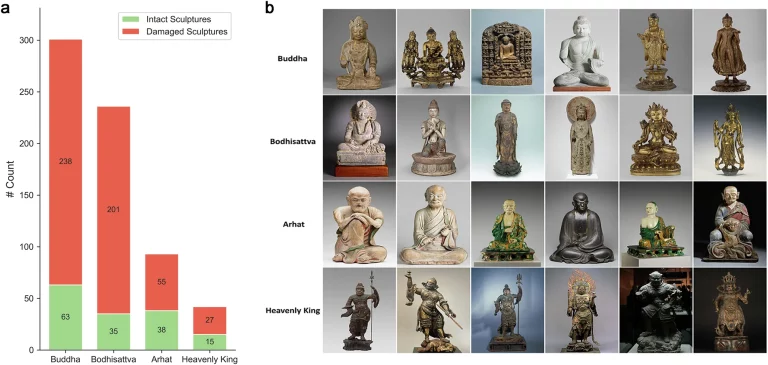

Preserving centuries-old Buddhist sculptures has long been a challenge for historians and conservationists. Fragile pieces, often hidden...

A 27‑foot sandstone Buddha will soon take the place of the High Line’s much‑talked‑about giant pigeon, marking...

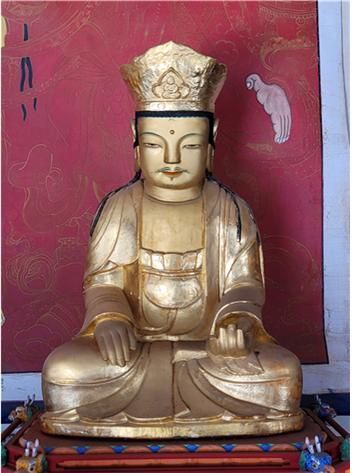

After years of preparation, the Chuncheon National Museum has opened a rare and quietly powerful exhibition tracing...

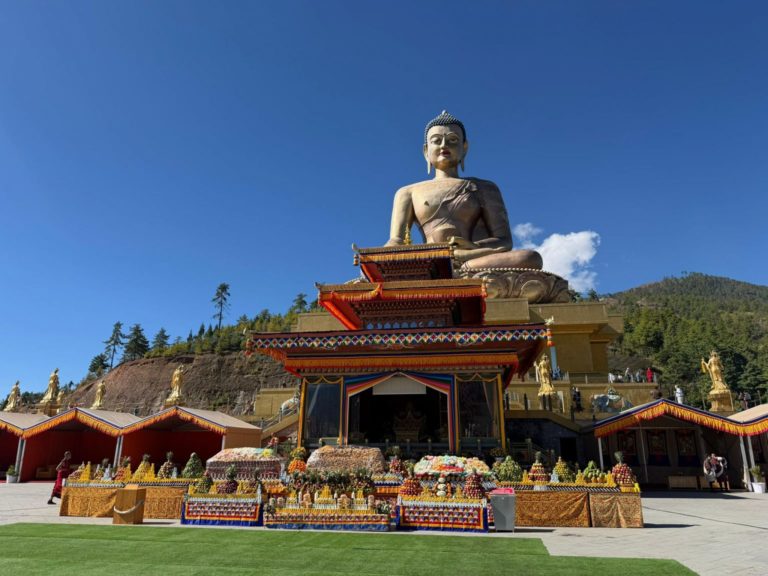

A major Buddhist ceremony has drawn crowds to Ba Den Mountain in Tay Ninh, where Vietnam has...