The Rubin Museum of Art’s popular installation, the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room, reopened to the public at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City on 11 June. The move follows the Rubin’s closure of its Manhattan space in October 2024 and represents a new chapter in its evolution as a “global museum” without a fixed location. The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room, which has attracted more than a million visitors since its debut in 2013, will remain at the Brooklyn Museum for a six-year residency until 2031.

The installation’s reopening took place on Saga Dawa Duchen, one of the most sacred days in the Tibetan Buddhist calendar, marking the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and passing into parinirvana.

The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room is now housed in the Arts of Asia Galleries on the Brooklyn Museum’s second floor, occupying 37 square meters. It was reconstructed using the original’s wooden posts, ceiling beams, and transparent glass doors. The intention, according to curators, was to preserve both the architectural integrity and spiritual ambiance of the original shrine room.

The Brooklyn Museum’s senior curator of Asian art, Joan Cummins, said: “We didn’t want the Shrine Room to be a thoroughfare,” referring to the space’s separation from the rest of the museum and city around it. (The New York Times)

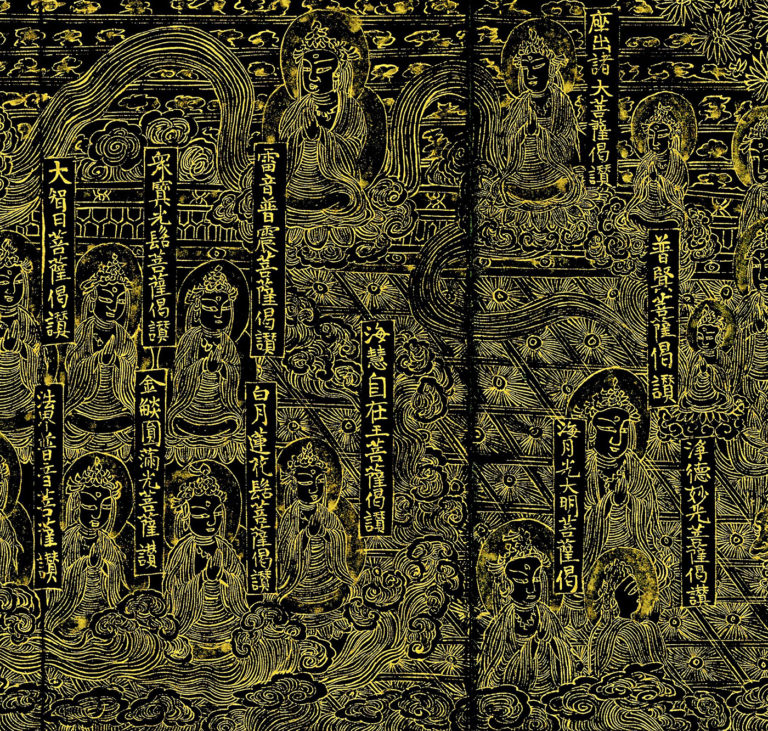

Visitors can encounter more than 100 Tibetan Buddhist artifacts spanning nine centuries, including thangkas, silver offering bowls, ritual instruments, and statues of deities. Among the most notable of the items is a 19th-century bejeweled image of the goddess Ushnishavijaya, associated with long life, and a 20th-century statue of Je Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelug tradition.

Curators have taken care to maintain as many elements of the original installation as possible. The room is infused with the scent of incense and the sound of recorded chants from Buddhist monks and nuns. Small stools are provided to encourage visitors to sit, reflect, and use the space as a site for meditation or quiet contemplation.

Senior curator of Himalayan art at the Rubin, and the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room’s curator, Elena Pakhoutova, recalled the devotion of frequent visitors: “There was one woman in particular who would come every day when the museum was open,” she said. “That was her practice.” (The New York Times)

The Rubin Museum of Art, which opened in 2004, has been a key institution for the public display and interpretation of Himalayan and Buddhist art in the United States. With the closure of its Manhattan building, the museum retained its collection and shifted its operations to lending works and curating traveling exhibitions. Now named the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, the institution aims to expand access to its holdings.

According to executive director Jorrit Britschgi, preserving the immersive quality of the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room was a high priority: “Standing in front of objects in something that was reminiscent of their original context is a very, very powerful experience,” he said. (The New York Times)

The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room installation at the Brooklyn Museum includes a digital touchscreen just outside the space, offering visitors interactive access to object descriptions and historical information. No labels are used inside the room itself to maintain the immersive experience.

Due to space limitations, the shrine room’s original set of richly painted Wrathful Shrine Doors from eastern Tibet, dated to the 19th century and depicting the fierce deity Mahakala, are displayed just outside the room. Mahakala is revered in Tibetan Buddhism as a protector of the Dharma.

The installation continues a curatorial practice initiated at the Rubin: rotating the objects every two years to reflect each of Tibetan Buddhism’s four main traditions. At the time of the Rubin’s closure, the room highlighted the Kagyu tradition. The current version features the Gelug tradition, following its emphasis on scholasticism and philosophical inquiry.

Many of the artifacts on display now have not been seen publicly since 2015, including a silk brocade thangka of the female buddha Tara, believed to offer aid in overcoming worldly concerns such as illness and fear.

“She tends to be someone that you pray to for sort of worldly worries, long life, health,” Cummins noted. (The New York Times)

New York City is home to a growing number of Buddhist communities, with an estimated 1–2 per cent of residents identifying as Buddhist according to Pew Research Center data. The Brooklyn Museum, known for its inclusive programming and accessible “pay-what-you-wish” admission policy, offers a fitting venue for the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room’s next life.

“It is transporting,” Cummins said of the installation. “It’s like stepping into Tibet for a moment.” (The New York Times)