By Dale Quarrington

You might not know the name of the statue. And you might not know the name of the temple where the statue is housed. In fact, you might not even know the city or the province where you might find this historic national treasure. However, once your eyes meet the “Stone Standing Maitreya Bodhisattva of Gwanchoksa Temple” you can’t help but feel its peaceful paradoxical peculiarity.

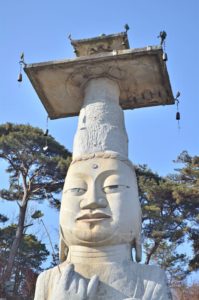

The “Stone Standing Maitreya Bodhisattva of Gwanchoksa Temple,” which is also known as the “Eunjin Mireuk-bul” [Future Buddha], is located at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province. The Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue stands an impressive 18.12 meters in height, and it was first made from 968 to 1006 A.D. Additionally, it’s the largest historic stone Buddha in all of Korea. The Eunjin Mireuk-bul has an oblong head with two piercing cat-like eyes. While meditative in disposition, it also appears otherworldly (almost alien). So while the statue may seem penetrating with its eyes, it also appears calm and tranquil. It appears to be a mysterious contradiction in its very composition.

The massive Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province / Courtesy of Dale Quarrington

The mysterious gaze of the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province / Courtesy of Dale Quarrington

Interestingly, the very history of the temple and the statue it houses is intermingled with several legends which play upon the paradoxical nature of the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue. In fact, the very founding of Gwanchok Temple has a legend connecting the founding of the temple with the construction of the statue.

According to this legend, a woman was picking wild herbs on Mount Banya, when she heard a baby crying. When she went to the spot where she heard the baby crying, there was no baby; instead, there was a large stone protruding out from the ground.

Learning this, the government ordered the monk Hyemyeong-daesa to make a Buddha statue from this large stone. Hyemyeong-daesa tried to build the Buddha statue employing some 100 artisans. However, when they attempted to stand the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue up, it was too large.

The massive Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province / Courtesy of Dale Quarrington

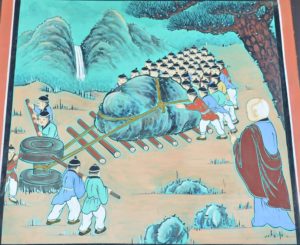

This mural at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province, depicts the founding myth of the temple. / Courtesy of Dale Quarrington

One day while out on a walk, Hyemyeong-daesa saw two child monks playing with a Buddha statue made of dirt. This statue was cut into three parts. After witnessing this, Hyemyeong-daesa rushed back to the temple and told the sculptors to make the ground flat. Following what he had just seen, he told the sculptors to place the bottom part of the statue first on the ground. Afterwards, the middle and upper portions of the statue were placed together to complete its full form.

With the statue now complete, it suddenly started to rain. And it rained for the next 21 days. It was said that there was auspicious energy surrounding the statue at this time and people saw a light shining forth from between the eyes of the statue.

The massive Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province / Courtesy of Dale Quarrington

This mural at Gwanchok Temple in Nonsan, South Chungcheong Province, depicts monks attempting to set upright the temple’s newly carved Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue. / Courtesy of Dale Quarrington

There is another imaginative legend involving the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue. One day, when China was at war with Korea, the Chinese made it all the way up the neighboring river next to Gwanchok Temple. The Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue disguised itself as a monk with a traditional bamboo hat. The statue then walked across the river so that the Chinese thought that the river was shallow. Thinking this, the soldiers jumped into the river and drowned. Angry, the Chinese general hit the statue’s bamboo hat with his sword, and the statue’s crown was broken. This part of the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue still remains broken to this day.

The paradoxical nature of the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue with its penetrating, yet peaceful nature, can even be seen in the modern history of Korea. Even though the statue is meant to represent peace and unity, the modern era of Korean history is arguably some of its darkest. And Gwanchok Temple, and the actions surrounding the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue, are certainly no exception to this dark past.

According to the Korea Review from 1905, a group of Koreans during the 1897-1910 Korean Empire reportedly damaged the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue. As a result, the monks demanded compensation first from a 12-year-old boy they caught damaging the statue. However, when they realized that the boy was an orphan, the monks turned to a Korean man in the crowd to recoup their damages. Unfortunately, the monks from Gwanchok Temple were unable to receive any form of compensation from this bystander.

After a while, a Japanese Buddhist monk came to live at Gwanchok Temple. This Japanese monk would be able to obtain some measure of influence over the Korean monks at the temple because of the nature of the Japanese/Korean relationship at this time. Both the Korean monks and the Japanese monk stormed the bystander’s house to confiscate things of value to compensate the temple for the previously damaged statue. It’s unclear if the monks were able to gain anything of value from the bystander’s house, but the incident didn’t end there. A Methodist missionary named William B. McGill, along with some of his Korean Christian parishioners, had built a church in the area. The Gwanchok Temple monks discovered that the bystander was a member of this church.

The monks contacted the local magistrate to challenge the church’s ownership of the land they occupied. The local Japanese residents and government officials stormed the church with guns, knives and clubs, completely destroying the church and injuring some of its parishioners. The violence finally ended when the Japanese police arrived. McGill complained later that none of the Japanese residents involved in the violence faced arrest.

This incident, which took place during a tumultuous time in Korea’s past after the signing of the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905 that made Korea a protectorate of Japan, served two purposes. First, it shows how Korean monks worked with Japanese Buddhists at this time to pursue and protect their own interests. On the other hand, it shows that Japanese Buddhists both ingratiated themselves with the local Korean monks, while also combating Christian missionary influences on the Korean Peninsula.

The juxtaposition found in the mysterious look of the Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue is blended beautifully with the blurring boundaries of reality found in the numerous legends of the temple. And adding to the conflicting nature of the statue is the divisiveness found in Korea’s recent colonial past. The Eunjin Mireuk-bul statue is a monument to what could have been and the potential to interpret the meaning of its gaze as it looks sublimely out onto the Korean landscape.

Unfortunately for now, or at least until next August, the statue is off-limits to the general public as it undergoes repairs. But the wait will hopefully be worth it.

Dale Quarrington has visited over 500 temples throughout the Korean Peninsula and published three books on Korean Buddhism. He runs the popular website, “Dale’s Korean Temple Adventures.”