I explored Korea’s vibrant history on Nov. 22 by going on a guided tour of the National Museum of Korea in Seoul with fellow Honorary Reporters. We gathered at the museum’s entrance at 7 p.m., ready to delve into the cultural tapestry within the facility’s walls.

This is the Ten-story Stone Pagoda from Gyeongcheonsa Temple in Seoul.

The tour commenced with the Ten-story Stone Pagoda from Gyeongcheonsa Temple in Seoul on the first floor, a relic dating back to 1348. What initially seemed like a replica was indeed the original artifact, intricately carved with Buddhist imagery and flowers. The innovative use of media art projected onto the pagoda brought the tower’s history to life, telling tales related to each of its 10 stories.

This queen’s golden crown and belt dates back to the Silla Kingdom.

Transitioning through the centuries, we explored a golden crown and belt worn by the queen of the Silla Kingdom unearthed in 1975 at a tomb in Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do Province. These royal artifacts not only showcased the elegance of Silla fashion but also symbolized royalty for the Silla queen, worn alongside elaborate gowns for occasions and even in death. The dangling carved images on the belt featuring fish, knives and jade indicated the elite social status of the wearer as well. Both the crown and belt featured intricate patterns and embossing, with the crown representing the pinnacle of Silla crown craftsmanship through its branch-shaped ornaments.

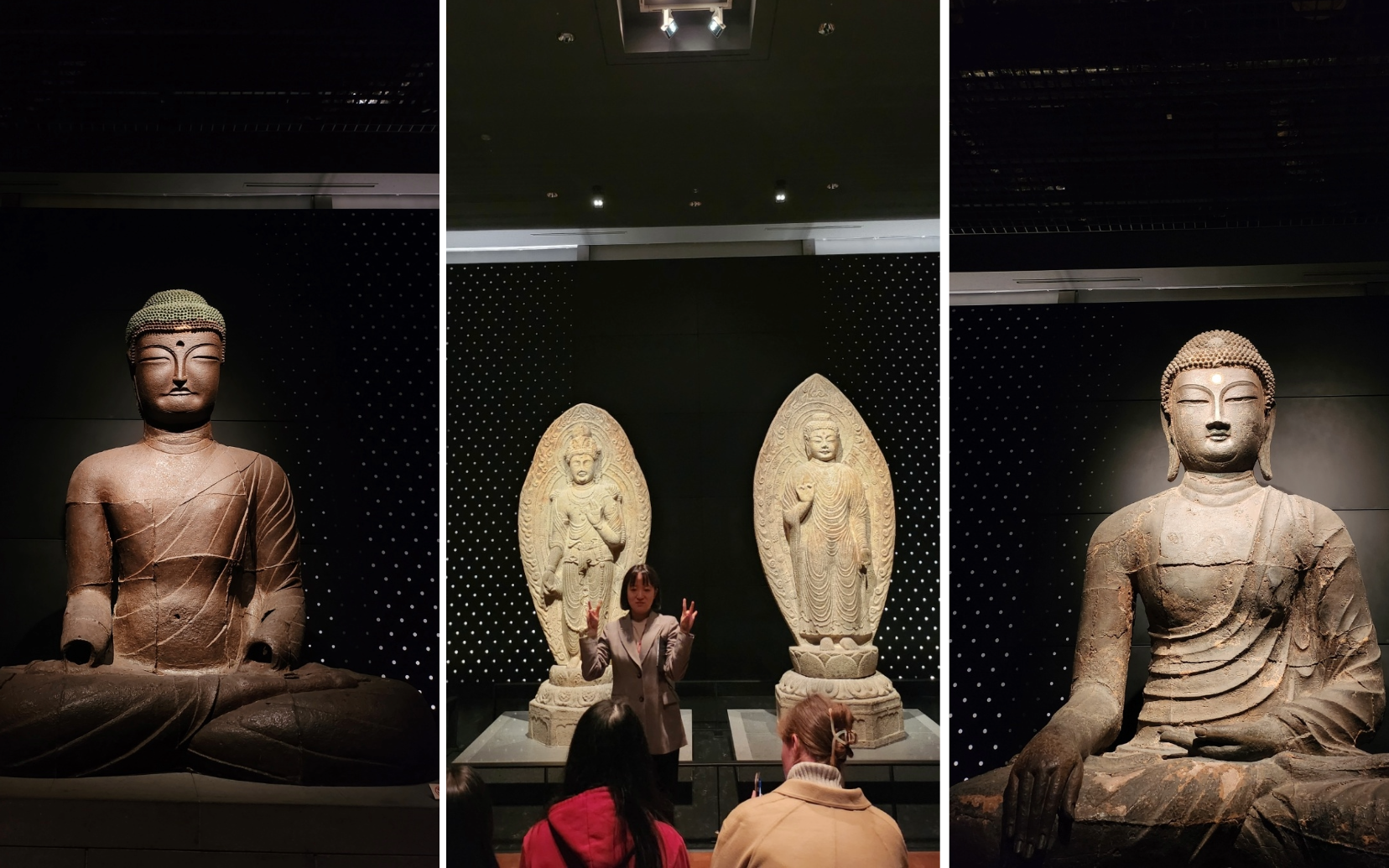

Shown from left to right are a cast-iron Buddha without hands from Bowonsa Temple in Seosan, Chungcheongnam-do Province; Stone Maitreya Bodhisattva and Amitabha Buddha from Gamsansa Temple in Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do Province; and the country’s largest iron Buddha statue found at a temple site in present-day Hanam, Gyeonggi-do Province.

A highlight of the tour was the Buddhist sculpture gallery displaying six statues from a range of periods and regions, attesting to the evolution of such statues’ craftsmanship over time and the unique characteristics by region due to the decentralization of power. The intricate details of each statue narrated the story of Buddha’s journey, reflecting the changes in styles and beliefs across eras.

The cast-iron Buddha without hands appeared to have a disproportionate face, but when viewed from below as intended by worshippers, the face seemed perfectly proportioned. The two stone Buddhas represented the stages of the Buddhist journey, the first adorned with jewelry and extravagant headwear symbolizing training and pursuit of knowledge and the other devoid of embellishment to signify true knowledge and enlightenment.

On the left is a celadon incense burner and on the right celadon boxes. Heading to the final stop on the tour, the ceramics wing, we were transported to the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties by seeing green celadon and white porcelain. Crafted during the Goryeo era from the ninth to 13th centuries, the celadon on display featured clay glazed with jade to achieve its distinctive green color. The celadon incense burner decorated with lotus flowers and rabbits symbolized wealth and prosperity. In the Goryeo era, the rabbits represented wisdom and fertility to exemplify the peak of the dynasty’s art.

This white porcelain moon jar is from the Joseon Dynasty.

Moving on from celadon, we transitioned to white porcelain, a hallmark of the Joseon period. In contrast to the intricate designs of celadon, porcelain embraced simplicity to symbolize the harmony of all natural elements and showcase technological progress. The white jar we saw, commonly referred to as a moon jar for its round shape resembling the moon, served a host of purposes such as holding flowers or wine, complementing rituals or decorating the homes of nobles. Its design evoked a sense of nobility, honor and self-cultivation, three core values of Joseon.

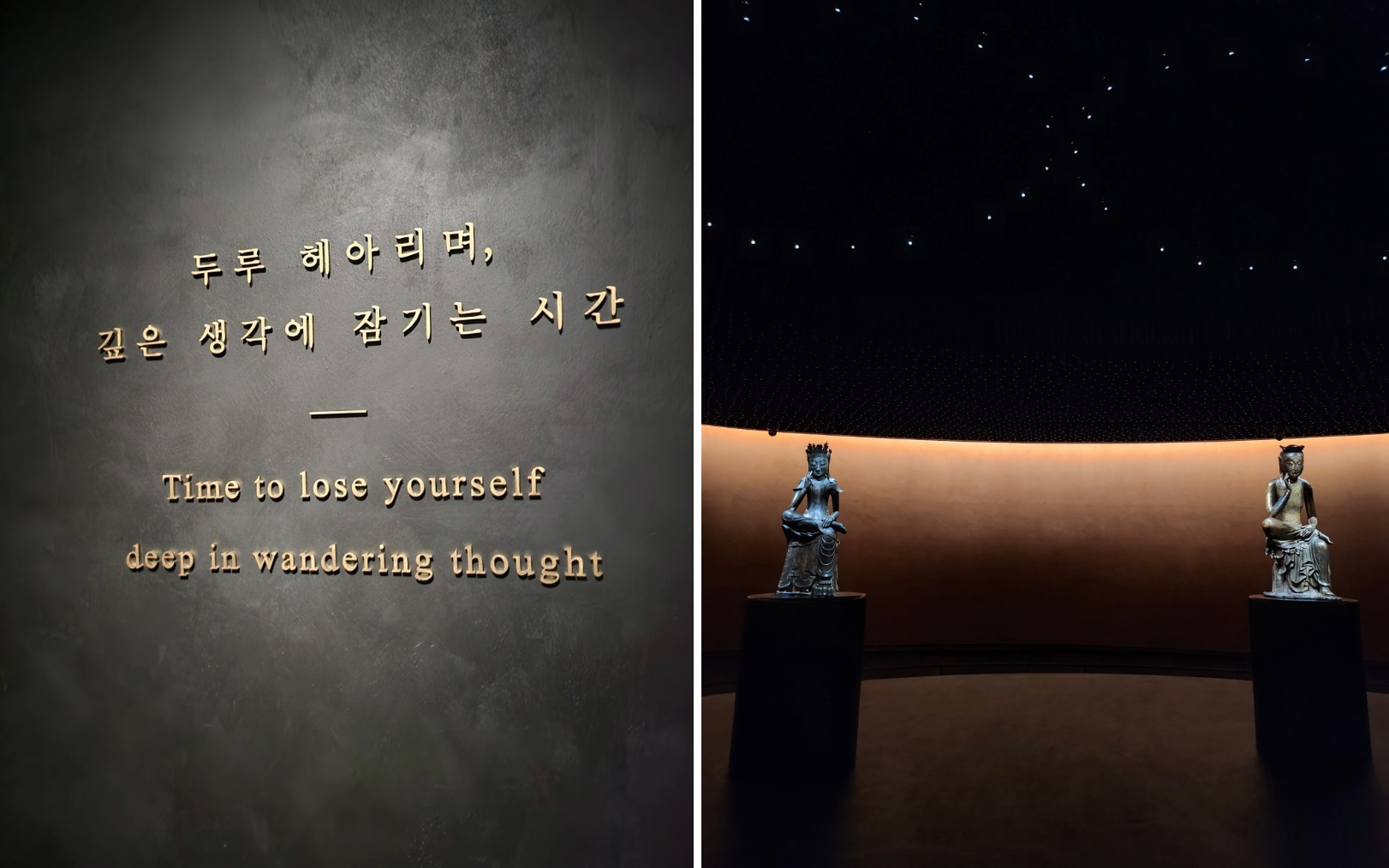

Left is an inscription at the entrance to the room of quiet contemplation and right are the “Pensive Bodhisattva” statues designated National Treasures No. 78 (left) and No. 83 in the room.

Our final destination was the room of quiet contemplation, another highlight for me. This dimly lit space features a high ceiling, ambient music and two introspective Buddha statues. Devoid of informational plaques or descriptions, the room displayed the “Pensive Bodhisattva” statues designated National Treasures Nos. 78 and 83 in an elevated fashion complemented by mood lighting and music.

Crafted from gilded bronze, the statues showcased the very essence of art through their placement. What struck me was the exhibit’s uniqueness, the decision to prompt contemplation alongside the Buddhas to allow visitors to form their own interpretations of their symbolism and significance. Representing enlightenment and contemplation on the aspects of birth, life, aging, sickness and death, these works spur visitors to craft their own narratives while conducting contemplation alongside the statues.

I found this tour to be more than just seeing relics but a holistic journey through Korea’s rich artistic tapestry. From the elegance of Silla royalty to the contemplative atmosphere of the room of quiet contemplation, each exhibit displayed a diversity that left a lasting impression on me and the rest of the Honorary Reporters who attended.