These five leading artists are offering new and intriguing takes on Buddhist imagery. For more, explore a selection of Buddhist art in the 17th Annual Lion’s Roar Auction, beginning November 13.

Rima Fujita, “Chödpa 2,” 2016. Mixed media on canvas, 58 x 46 inches. Art © Rima Fujita

Rima Fujita

A descendant of samurai, Rima Fujita was born in Tokyo, lived in New York City for thirty-two years, and now resides in California. She’s internationally recognized for her method of working with vibrant colors on black canvas and was described by the Dalai Lama as “an artist who creates beautiful art.” Fujita’s works often express a sweet otherworldliness and kindle feelings of yearning and stillness in the viewer. She draws inspiration from her dreams and meditation practice as well as Buddhist and Bushido philosophies. Her picture books include Save the Himalayas, The Day the Buddha Woke Up, and the recently released The Extraordinary Life of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. In 2001 she established Books for Children, an organization that produces children’s books in Tibetan and donates them to Tibetan refugee schools in India, Nepal, and Bhutan.

Bill Viola

Bill Viola, “Catherine’s Room,” (detail), 2001. Color video polyptych on five LCD flat panel displays mounted on wall, 15 x 97 x 2 1/4 in. 18:39 minutes. Performer: Weba Garretson. Photo of work by Kira Perov. portrait by Jonty Wilde.

Inspired by Zen Buddhism amongst other spiritual traditions, Bill Viola’s video installations focus on the experiences of birth, death, and unfolding of consciousness. Since the early 1970s, Viola has used videos of water imagery, human forms, and light (often rendered in slow motion) to investigate the marvels of insight as a pathway to wisdom. It is the sense of serenity he expresses in his work that separates Viola from other video artists. During a 2004 interview, Viola described discovering Buddhism in Japan. “The sense of a palpable stillness and silence, reflected in the serene image of the Buddha’s face, was so different from my memories of being in church,” he said. “This left an even deeper impression than the art and architecture I was ostensibly there to see…. During that period I had several experiences that changed my life and my understanding of art and its place in spiritual practice.”

Kazuaki Tanahashi

Kazuaki Tanahashi, “Enso,” 2002. Acrylic on paper.

There’s no mistaking a Kazuaki Tanahashi enso. Sometimes called “a Zen circle” in English, an enso symbolizes enlightenment. Creating an enso can be a contemplative art, while the final product can serve as a meditation aid. They’re most often rendered, using one or two strokes, on white paper with black ink, but Tanahashi creates vibrant ensos in oceanic blues and greys or fiery reds and oranges. He was born in Japan in 1933 and, as a boy, studied with Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido. Today, Tanahashi is a trained calligrapher known as “the pioneer of one stroke painting.” “The quality of the line is what matters most—how deep, strong, or honest it is,” he explains. “If your personality is interesting enough, the line will be interesting. To do this, you have to be fearless.” Tanahashi is also a Zen teacher, author, activist, and translator of Buddhist texts, most notably of works by Dogen.

Tsherin Sherpa

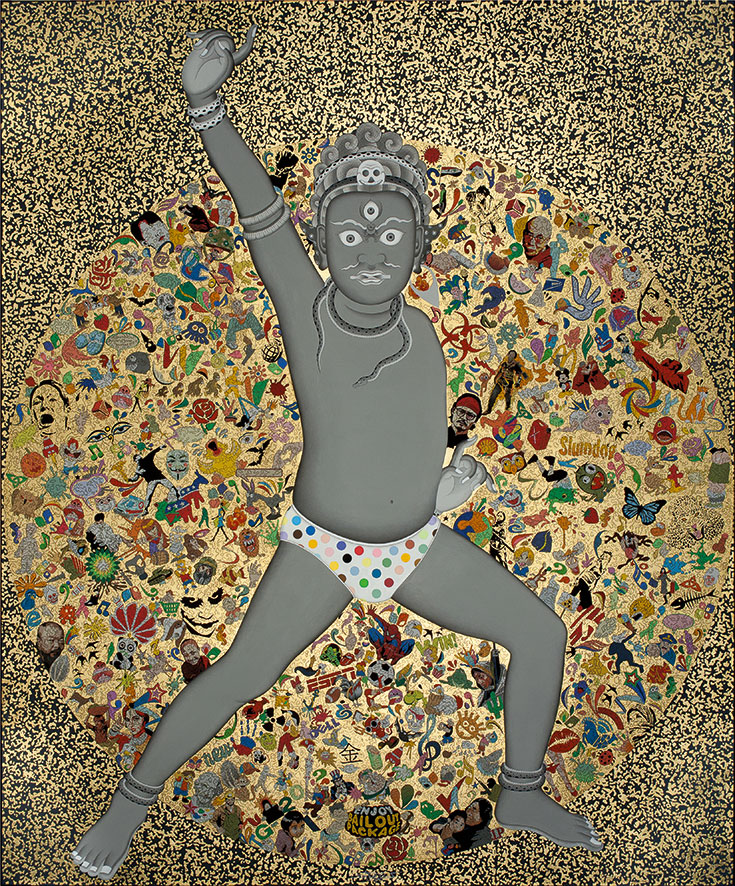

Tsherin Sherpa, “If You’re Happy and You Know it…Clap Your Hands,” 2012. Gold leaf, acrylic and ink on linen, 58 x 48 inches

Having studied Tibetan thangka painting since age twelve, Tsherin Sherpa mixes the modern with the ancient, the sacred and the silly. Traditional thangkas can depict Buddhist deities, the wheel of life, images of the Buddha, and mandalas. Sherpa’s paintings reimagine the thangka, incorporating secular motifs and symbols in playful, startling ways. (Think deities in polka-dotted underwear.) Sherpa grew up in Kathmandu, near the Boudhanath Stupa, a sacred Buddhist site, but moved from Nepal to California in his thirties where he’s found himself fascinated by America’s barrage of advertising imagery. In an interview with the Asia Art Archive in America in 2011, Sherpa reflected on why early Buddhist artists created Buddhist artwork. “Were these early painters actually trying to use this image to preach or inspire?” Sherpa asked. “Now…I’m making these images to pay my rent! It is ironic how over time, the image has become more of a commodity…. Its purpose has transformed.”

Michela Martello

Michela Martello, “Future is Goddess,” 2017. Pigment, acrylic, antique lace on Torsello, vintage Italian hand woven linen, 108 x 38 inches

“Symbols are magic to me,” Michela Martello exclaims in an artist statement. “Learning Buddhist teachings made symbols more apparent. They form a mysterious and refined language at times deep, at times on the surface, until suddenly their story appears from the unconscious.” The Italian artist’s kaleidoscopic pieces are rife with symbolism. Take for example her version of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. In Martello’s painting, Venus is a blue dakini carrying a Tibetan snow lion in her womb, representing the Shakyamuni Buddha. Martello, who frequently depicts empowered female imagery in her work, weaves the threads of Buddhism and feminism and incorporates quilts, pages from Shakespeare, the skulls of animals, even human hair. “Everything that surrounds me is essential to my work,” she continues in her statement. “Discovering what I am and what I want to transmit on canvas, and following the thread of pauses and silence, becomes the fuel of my painting practice.” *