Angkor Wat attracts millions of visitors a year, but most know little of the intricate and vast water system that fed the empire’s rise and demise.

Every April during Khmer New Year celebrations, Sophy Peng, her four siblings and parents make the pilgrimage to Cambodia’s most sacred mountain, Phnom Kulen. As the birthplace of the mighty Angkor Empire, fabled Kulen’s gentle slopes hold a special place in the hearts of locals.

During religious festivals, Cambodians flock to its peak to be blessed by the same waters used to coronate kings since 802 AD. This was when empire founder Jayavarman II was washed with sacred water and declared a devaraja or God King, marking the start of the Angkor Empire. The empire went on to span much of modern-day Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam, and house the world’s largest pre-industrial urban hub – the city of Angkor.

To immortalise this sacred spot that sits about 50km north of Siem Reap city, 1,000 lingas – a phallic symbol incarnation of the Hindu god Shiva – were carved into the riverbed at Kbal Spean, where water flows to the Angkor plains and into the Tonle Sap Lake. Even today, this water is regarded as sacred, and its power is believed to cure illnesses and bring luck.

“This is a very special place for Cambodians; it’s an important part of our history,” said Peng. “Every year, my family visit Mount Kulen as part of our Khmer New Year rituals. We bring food donations to leave at the temple and pour water from Kbal Spean on us to bring good luck.”

Story continues below

The carved riverbed at Kbal Spean is set deep in the jungle to the north-east of Angkor (Credit: GoodOlga/Getty Images)

The carved riverbed at Kbal Spean is set deep in the jungle to the north-east of Angkor (Credit: GoodOlga/Getty Images)

Jayavarman II’s spiritual blessing marked the start of the Angkor Empire’s close relationship with water. However, it wasn’t until the capital shifted south to Rolous and then to its final resting place for more than five centuries – Angkor – that master engineers were able to use their skills to create the intricate water system that fed the empire’s rise and demise.

“The plains of Angkor are ideal for an empire to flourish,” explained Dan Penny, a researcher in the geosciences department at the University of Sydney who has extensively studied Angkor. “There are ample resources, such as good rice soil close to the Tonle Sap Lake. The lake is one of the world’s most productive inland fisheries and Angkor is sitting right on the north shore of this enormous food bowl. Angkor grew to become a success on the back of these resources.”

In the 1950s and ’60s, French archaeologist Bernard Philippe Groslier used aerial archaeology to reconstruct the layout of Angkor’s ancient cities. This revealed its vast reach and the complexity of its water management network and led Groslier to dub Angkor the “Hydraulic City”.

Since then, archaeologists have carried out extensive research into the water network and the vital role it played. In 2012, the true extent of the hydraulic system, which spans 1,000 sq km, was revealed through airborne laser scanning technology (LiDAR) led by archaeologist Dr Damian Evans, a research fellow at École Française d’Extrême-Orient.

“The missing pieces of the puzzle came into sharp focus,” said Dr Evans. “We’re working on a paper now which is the final definitive map of Angkor and shows the real picture, including the hydraulic system. Water was one of the secrets to the empire’s success.”

The Angkor Empire spanned much of modern-day Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam (Credit: Richard Sharrocks/Getty Images)

The Angkor Empire spanned much of modern-day Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam (Credit: Richard Sharrocks/Getty Images)

To craft a city of its size, the manmade canals carved to steer water from Phnom Kulen to the plains of Angkor were key to construction. They were used to transport the estimated 10 million sandstone bricks, weighing up to 1,500kg each, that built Angkor.

As well as ensuring a year-round water supply in a monsoon climate to support the population, agriculture and livestock, the hydraulic system feeds the foundations that have kept the temples standing for centuries. The sandy soil alone is not enough to withstand the weight of the stones. However, master engineers discovered mixing sand and water creates stable foundations, so the moats that surround each temple were designed to provide a constant supply of groundwater. This has created foundations strong enough to keep the temples stable and prevent them from crumbling all these centuries later.

Throughout the empire’s history, successive kings expanded, restored and improved Angkor’s complex water network. This comprises an impressive web of canals, dykes, moats, barays (reservoirs) – the West Baray is the earliest and largest manmade structure that can be spotted from space, at 7.8km long and 2.1km wide – as well as master engineering to control water flow.

There are many examples of historic cities with elaborate water management systems, but nothing like this

“Angkor’s hydraulic system is so unique because of its scale,” said Penny. “There are many examples of historic cities with elaborate water management systems, but nothing like this. The scale of the reservoirs, for example. The amount of water the West Baray holds is incredible. Many European cities could have comfortably sat within it when it was built. It’s mind-boggling; it’s a sea.”

However, while it was water that contributed to the Angkor Empire’s rise, it was also water that contributed to its demise. “It’s clear the water management network was really important in the growth of the city and led to wealth and power,” said Penny. “But as it grew more complex and larger and larger, it became the Achilles heel to the city itself.”

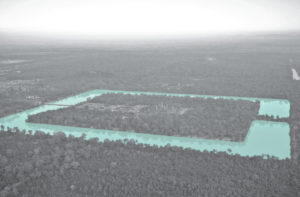

Master engineers created the intricate water system that fed the Angkor Empire’s rise and demise (Credit: Boy_Anupong/Getty Images)

Master engineers created the intricate water system that fed the Angkor Empire’s rise and demise (Credit: Boy_Anupong/Getty Images)

Research reveals that in the late 14th and early 15th Centuries, dramatic shifts in climate caused prolonged monsoon rains followed by intense droughts. These climate changes took their toll on the water management network, contributing to the mighty empire’s eventual fall.

“The whole city was being slapped around by these huge weather variations,” said Penny. “The scale of the network and its interdependence meant the massive disturbance of droughts and people changing the system to cope followed by very wet years blew parts apart. This fragmented the whole network, making it unusable.”

Further research suggests these weather shifts, combined with the breakdown of the hydraulic system and increasing attacks from the neighbouring Siamese, caused the capital to shift south to Oudong.

“The history books tell you the end of Angkor is because the Siamese overran it in 1431,” said Dr Damian. “I don’t think that happened. The evidence we have indicates it was more long-term. The pressure of huge droughts, the water management system breaking down, constant attacks from the Siamese and the expansion of maritime routes all contributed.”

Regardless, once Angkor was abandoned, it was reclaimed by nature. While locals were aware of the ancient monuments, they were shrouded by jungle from the rest of the world until 1860, when they were “rediscovered” by French explorer Henri Mouhot. This sparked a series of huge restoration projects that continue today.

In the last two decades, Cambodia has seen a huge increase in tourists flocking to Angkor Wat Archaeological Park to stand in the shadows of Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm and Bayon temples. In 2019, 2.2 million people explored the site. The surge in hotels, eateries and visitors put huge pressure on water demand, causing drastic shortages. As the temples rely on a constant groundwater supply to remain standing, this sparked concern over the preservation of the Unesco-listed site.

Abandoned in the 15th Century, Angkor was only “rediscovered” in the 1860s (Credit: Kriangkrai Thitimakorn/Getty Images)

Abandoned in the 15th Century, Angkor was only “rediscovered” in the 1860s (Credit: Kriangkrai Thitimakorn/Getty Images)

The increase in water demand coupled with severe monsoon flooding from 2009 to 2011, triggered a mass restoration of the ancient water system. Socheata Heng, who owns a guesthouse on the outskirts of Siem Reap, recalled the 2011 floods – the province’s worst in 50 years. “It caused so much damage,” she said. “Crops were destroyed, communities had to be evacuated and the water came pouring into my guesthouse. It was devastating.”

Headed by APSARA National Authority, which is tasked with protecting Angkor Archaeological Park, the restoration project has seen many of the hydraulic system’s barays and waterways renovated, including Angkor Thom’s 12km moat, the West Baray and the 10th-Century royal basin, Srah Srang. These efforts have helped combat the water shortages triggered by the sharp rise in tourists, and also prevent the severe flooding experienced across the province between 2009 and 2011.

This means today, the vast system that dates back centuries continues to satisfy Siem Reap’s thirst by providing a constant water supply, preventing destructive flooding and providing the foundations that will keep Angkor’s sacred temples stable well into the future.

“The renovation of the barays and water systems provides water for irrigation, so they have become part of today’s agrarian landscape while also helping stabilise the temples,” said Dr Evans. “It’s truly incredible this water management system still serves Siem Reap.”

Ancient Engineering Marvels is a BBC Travel series that takes inspiration from unique architectural ideas or ingenious constructions built by past civilisations and cultures across the planet.

—

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.