One of the world’s most remarkable—and little known—empires comes to life in south India with new heritage tours.

The only thing left of the grand city of Gangaikondacholapuram in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu is a temple amidst paddy fields. But for a time, it was an epicenter of medieval Southeast Asia and the capital of one of the oldest and longest ruling dynasties in the world.

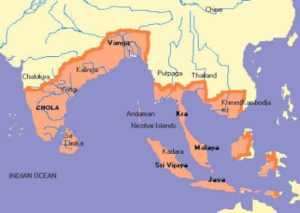

For nearly five centuries, the Chola dynasty (300 B.C.–A.D. 1279) asserted its power—influencing religion, culture, and architecture—via a sophisticated maritime trade system that extended from India throughout Southeast Asia and even to China.

Yet, despite the kingdom’s extensive trade route system and widespread power, the Cholas remained shrouded in mystery for centuries, while later invaders like the Mughals and British gained prominence in India’s larger academic and cultural history.

Now, technology-backed excavations, custom Chola heritage tours, and a record-breaking Indian film have rekindled interest in the Cholas, creating opportunities for travelers to help solve one of history’s greatest mysteries: What happened to the empire?

The golden age

The Cholas were one of the three most powerful Tamil kingdoms in medieval southern India. At the empire’s zenith, Chola kings invested in art, literature, education, and architecture. They ambitiously built massive stone temples—which served as cultural and social hubs—adorned with elaborate sculptures and detailed paintings, and they designed man-made lakes to alleviate droughts and provide a supply of safe drinking water.

Ornate pointed structure covered in hundreds of small statues

Brihadisvara Temple, a revered religious site for Hindus in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India, was built by King Rajaraja Chola I in A.D. 1010. With an imposing 216-foot-tall stone pyramidal spire, the temple is considered one of India’s greatest architectural marvels.

But little is left of their capital city, Gangaikondacholapuram (meaning the City of the Chola who conquered Ganga). The only visible proof of its legacy are Gangaikondacholisvaram (also known as Brihadisvara Temple), a UNESCO World Heritage site, and the three-mile-long Cholagangam (now Ponneri) Lake.

In 2021, archaeologists uncovered the first major physical evidence of a grand palace in the ancient capital city, says K. Sridharan, an archaeologist who was part of the first excavation team in the 1980s.

“There are mentions of Gangaikondacholapuram only in copper plates, a few Tamil literary works, and epigraphs on the walls of the temples built by the Cholas, including those at Gangaikondacholisvaram,” says Sridharan. He says the details that could provide clues about the city layout and the lives led by its inhabitants remain elusive. “Any shred of physical evidence found is exciting.”

Historians are still unraveling why the city and its people disappeared in the 13th century, but many believe that an invasion led by a rival kingdom in the latter half of the century may have played a part.

“Jatavarman Sundara Pandya of the Pandya dynasty had invaded places nearby Gangaikondacholapuram. He must have razed the city to the ground, sparing just the temple,” says Chitra Madhavan, an author and a historian. She adds that Hindu kings often spared religious sites during war. “As the later Cholas shifted their capital back to Thanjavur, people must have migrated to other places for better prospects,” she says.

Zoom in to see all the locations featured in this story.

Although little remains of the Cholas’ capital city, travelers can still learn about the dynasty throughout Tamil Nadu. Several sites highlight the Cholas’ impact on bronze casting, architecture, and music. New hertiage trails have sprouted up thanks to the national popularity of the film Ponniyin Selvan-1, says historian Jayakumar Baradwaj, who specializes in Chola heritage tours.

Multi-armed human like figure holds various objects

Human figures carved into the walls of Gangaikondacholapuram temple

A rich repository of intricately carved sculptures of Hindu deities decorate the walls of Gangaikondacholisvaram Temple. The ones pictured here show an incarnate of Shiva alone (left) and with his wife, Parvati (right), placing a crown of flowers on King Rajendra I’s head.

“Gangaikondacholapuram may be a small village today, but it is from here that the Cholas had once ruled almost the whole of southeast Asia,” he says.

The movie also inspired the new “Ponniyin Selvan” trail. The three-day tour developed by the Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation takes visitors from Chennai, Tamil Nadu’s capital, to several places significant to Chola history, including Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur and Veeranam Lake.

For travelers looking to pave their own way, head an hour southwest of Gangaikondacholapuram to the remote village of Swamimalai, where millennium-old Chola bronze foundries offer a peek into the art of making utsava murtis, portable idols, in bronze using the lost-wax process, a technique perfected and popularized by the Chola.

“You are bound to find at least a piece or two of these Chola bronzes in prominent museums of the world like New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, London,” says S. Vijay Kumar, who leads a team of online sleuths working to recover stolen artifacts for the India Pride Project.

Kudavayil Balasubramanian, former curator at the Saraswati Mahal Library—one of the oldest libraries in Asia, located inside the Thanjavur Maratha Palace—adds that a substantial collection of bronze and stone Chola sculptures from the 9th through 13th centuries can be found in the palace’s art gallery.

From elaborate murals depicting Hindu epics and delicately carved granite sculptures to soaring towers and spires (some still the tallest in India to date), the 11th- and 12th-century temples collectively known as the “Great Living Chola Temples” offer a unique perspective on how Chola art and architecture evolved over the centuries.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987, the massive Brihadishvara Temple in Thanjavur, Airavatesvara Temple in Dharasuram, and Gangaikondacholisvaram in Gangaikondacholapuram remain active places of worship, using the same rituals established and practiced over a thousand years ago.

Steps from Brihadishvara Temple in Thanjavur, travelers can tour the workshop where India’s national musical instrument, the Saraswati veena, is made. Named after the Hindu goddess of learning, art, and wisdom, the Saraswati veena is a descendant of the ancient yazh, a harp-like stringed instrument created during the Chola dynasty.

These experiences are just the tip of the iceberg, says Vijay Kumar.

“The naval prowess of the Cholas has been a surprisingly neglected area of study, when the truth is that South Indians, especially the Tamils, have been seafaring pioneers for much longer,” he says. “Excavations in Malaysia, Indonesia, and even Myanmar may throw many more surprises our way.”