This essay is a preliminary to the study of the modern Sinhala Buddhist civilization of Sri Lanka. This essay draws attention to those aspects of Asia’s Buddhist civilization, which are not well known and have not received much attention in Sri Lanka.

Buddhism, which originated in north India in the 6th century BC, spread over most of South and Southeast Asia, creating a vast Buddhist civilization, which included many sovereign states of today. Sri Lanka played an important role in preserving Buddhism and in spreading Buddhism within this region.

Buddhism held a monopoly position in Asia until the 16th century. In the 16th century, South and Southeast Asia went under Muslim rule and then Christian rule. Sri Lanka had 450 years of Christian rule, during which Sri Lanka’s Buddhist heritage came under attack. Buddhism returned to its ‘rightful place’ after independence in 1948, to the open resentment of the other religions, which had been given entrenched positions by the foreign rulers.

Buddhism is the only atheist (non-God) religion among the three world religions[1]. This makes it unique. Buddhism does not speak of a God and does not call for the assistance of a God in human affairs. It did not say, as other religions did, that a God figured in the creation of the world. Buddhism has no theory of creation. In addition, Buddha said he was not a messenger, incarnation or a prophet of God. He was not a supernatural being at all. He was plain human and if he could achieve Buddhahood, so could others.

Buddhism was very much a product of the Indian thinking of its time. India in the 6th century BC was teeming with various philosophical ideas. It was in a veritable religious and philosophical ferment, said Ananda Guruge. The public changed faith frequently and there was competition for followers. When they met, people asked each other, ‘who is your teacher’.

The most important contribution of Buddhism to this medley was its focus on the individual, on analytical thinking and on the control of the mind. However, concentration of the mind is only a means to an end. Buddhist teachings are a raft to be abandoned later, said the Buddha. Buddha played a pioneering role in concept formation in Indian philosophy, said Guruge.

Buddhism begins with the present, with the empirical observations of human existence. But these were given a new twist. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus said ‘one cannot step twice into the same river’. Buddha said ‘the same man cannot step twice into the same river’.

Nirvana was the goal, but that was far away. What were Buddhists to do till then? Lay Buddhists were advised to carry out duties and obligations which ensure harmony and common good. Buddha was as concerned with saving and investment of capital as with the duties of a ruler and duties one owes to ones parents, family, friend, and even servants, said Guruge.

Buddha found it advisable to build on the existing knowledge and use the vocabulary that existed. Buddha incorporated some of the existing philosophical ideas into his own doctrine. These include the theory of samsara, rebirth, Karma and meditation. Anthropologists have sneered as Sri Lankan Buddhists saying that they imagine that Buddhist concepts, especially Karma, are unique to Buddhism.

Buddha used the existing vocabulary, as well, but gave the words new meanings. He used ‘Tevijja’ to mean Buddhist knowledge not the three Vedas. He gave new meanings to ‘arahant’, ‘dharma’, ‘atman’, ‘Samadhi.’

Buddhism arose long after Brahmanism was established in India. The Vedas had been organized into the three Samhitas and the Vedic literature, such as the Upanishads, had been written long before Buddhism appeared. But it is doubtful whether the Buddha was exposed to the full impact of this literature, said Guruge. The Vedic teachings were known only to a limited group. and the part of India in which the Buddha lived was on the periphery of the Vedic civilization. The Buddhist canon therefore shows only a vague acquaintance with the Vedic literature, said Guruge.

Buddha’s preachings were directed towards the intelligent listener. The doctrine of Anatta was not intended for those who are dull, because they will fall into the error of nihilism, Buddha said. Buddhist learning consisted of progressively difficult mental exercises. Buddha had designed individualized courses of meditation for his disciples according to each ones personality. In Majjhima nikaya, Buddha compared his teaching to training a horse or elephant, learning archery or accountancy.

Buddha was a skilful teacher. His discourses were planned with meticulous care. There was an orderly presentation of ideas, said Guruge. Beginning with an attention catching statement he analyses a Buddhist concept into its constituent elements. He posed a battery of questions aimed at convincing and leading his listeners gradually to his point of view. He sets tasks which made people arrive at conclusions, by their own efforts.

Buddha’s teachings had been committed to memory and classified during the time of the Buddha itself. Scholar monks recorded the utterances of the Buddha and his disciples and classified them, said Guruge. Commentaries began to appear in the Buddha’s life time. And when the first Buddhist Council was held within three months of the death of Buddha, disciples were able to have a ‘general rehearsal’ of all teachings and examine its codification and classification, reported Guruge. A body of knowledge divided into Vinaya and Dhamma had emerged.

There was other literary activity going on. Indices, tables of contents, summaries and annotated references were prepared to keep track of the growing mass of sayings, sermons, discourses, debates, clarifications, interpretations, elucidations, expositions as well as poems. There were mnemonical summaries to facilitate recall and a proper system of indexing. All this literary activity commenced in the time of Buddha, presumably under his direction, said Guruge.

Buddha used the Magadhi language for his teachings. These sermons were later converted to Pali language . Pali was a literary language , not a spoken one and it showed many divergences from Magadhi , said Guruge. The word Pali means ‘text’.

Guruge gives us information on Gautama Buddha as a person. The Buddha was not the austere person some western scholars have attempted to show, Guruge said. Buddha could appreciate good music and had commented favorably on a love lyric.

Buddha had a fine aesthetic sense. He saw the beauty of a well laid paddy field and ordered the monks to sew their robes in a similar design. Buddha chose beautiful sites for his stops during missionary activities. Donors should construct beautiful monasteries and gift them to the monks, Buddha said in the Chullavagga.

The Buddha was a persuasive orator, whose powerful verbal onslaughts on opponent and lucid and eloquent explosions of moral and spiritual values were worth of record and repetition. Similes drawn from everyday life made his discourses picturesque. He delved into legend and history for anecdotes and illustrations. He made apt use of dramatization and visual aids drawn from the environment.

He was a poet of extraordinary talent, whose picturesque language, figures of speech and simple metrical compositions had a permanent appeal, said Guruge. Buddha presented his ideas in metre, usually a quatrain of 32 syllables. Around the Buddha was a galaxy of equally gifted poets.

Buddha was a great story teller, and his repertoire, judging by the Buddhist literature, was enormous, continued Guruge. He could create or recall a story to suit every occasion. Buddha delved deep into the vast folk literature of India for stories and anecdotes which he cleverly adapted to illustrate doctrinal points. The Jataka stories are a collection of 547 Indian stories which become Buddhist only because the main characters are connected to the Buddha. The Hindu and Jain stories are also based on this common source of Indian folklore, Guruge added.

Buddha did not appoint a successor, nor did he create an ‘administrative set up’. Buddha had no pre conceived plan for the Sangha either. The Sangha evolved gradually. Rules were laid down for the Sangha as and when situations arose. But a vibrant Sangha was created. It proved to be a resilient organization with a proven capacity for self regeneration.

The Sangha were effective teachers. Moggalana had illustrated a talk on dependent origination using the diagram of a wheel. This became a popular motif in Nepal and in the Tangka paintings of Tibet.Monks and nuns prepared their own sermons and even composed poetic appreciations of their way of life, as in Thera-theri gatha.

Monks were expected to have a good memory, legible well rounded hand writing, and clear speech.In all Buddhist countries parents sent their children to the Buddhist temple to learn akuru, said Guruge.

Monks also had a wide range of manual and technical skills. They knew something of wood work, masonry, and metal work. In Tibet monks studied carpentry, masonry, sewing and embroidery as well as their religious subjects.

The Sangha consisted of women as well as men. The bhikkhuni order was created soon after the bhikkhu order.In the Vinaya Pitaka there is a separate Bhikkhuni vibanga. A collection of scriptures concerning the role and abilities of women in the early Sangha is found in the fifth division of the Samyutta Nikaya, known as the Bhikkhunī-Saṃyutta . A number of the nuns whose verses are found in the Therigatha also have verses in the book of the Khuddaka Nikaya known as the Apadāna.

An important feature of Buddhism was the creation of monasteries. Settled life within monasteries promoted the pursuit of study , debate, discussion teaching and research. There was intellectual liberalism. The Buddha asked the monks to avoid tradition, dogma, subject everything to critical examination, including his own teachings.

A distinctive feature of Buddhist education in the monastery was its individual cantered learning. Teacher met each pupil individually, not in a class taught collectively by teacher. Student spent time in self learning, using commentaries, glossaries, indexes and lexicons. He had to provide an original composition in the final exam.However, no student was considered a failure in monastery. An average student was given the task of memorizing material or printing texts for dissemination.

As Buddhism evolved into an organized religion, there was a need for a permanent record of its activities and donations received as well. This led to the well known Buddhist tradition of record keeping.

There was a substantial Buddhist literature..The missionary outlook, the monastic organization and the intellectual interaction of highly motivated men and women provided an ideal climate for intensive literary activity, observed Guruge.

In addition to the Buddhist philosophy, the literature consisted also of secondary material. Thera gatha” is written by monks, starting with those who lived during the time of the Buddha. The collection has continued to grow until at least the Third Buddhist Council. Many of the verses are on the attempts of monks to overcome the temptations of Mara. One set of verses is recited by the reformed killer Angulimala. Verses mirror contemporary secular poetry of their time, with romantic lyrics replaced with religious imagery.

Theri gatha is a collection of short poems by senior Bhikkhunis. They also start in the late 6th century BC and go on for the next 300 years. They were composed orally in the Magadhi language and were passed on orally until about 80 B.C.E., when they were written down in Pali. It is the earliest known collection of women’s literature composed in India.

The Therigatha contains passages reaffirming the view that women are equal to men in terms of spiritual attainment . It also contains verses that address issues of particular interest to women in ancient South Asian society. There are verses of a mother whose child has died ,a former sex worker who became a nun, a wealthy heiress who abandoned her life of pleasure and even verses by the Buddha’s own aunt and stepmother, Mahapajapati Gotami . One verse is spoken by a woman trying to talk her husband out of becoming a monk.

The Buddhist doctrine was formalized in the three Councils held after the death of the Buddha. The first Council was held at Rajgir under King Ajatasattu (492 to 460 BC) three months after the death of the Buddha. A major part of the Sutta and Vinaya pitaka were decided at this Council.

Second council was at Vaisali, under King Kalasoka (395 – 367 BC) hundred years after death of Buddha, This council met to discuss disputes regarding Vinaya rules. By this time, new schools of Buddhism had developed. These breakaway groups were present at this Council. Their first set of disagreements was on how to interpret the Vinaya rules, and then they went on to doctrinal differences.

The Third Council was Pataliputra, under Dharmasoka (268 – 232 BC). This was a very Important Council. The Theravada canon which we have today was decided at this Council. At this Council too, there were differences of opinion between the various Buddhist schools. The Sarvastivada and Mahasanghika schools attending this Council later helped to develop Mahayana.

There are three major Buddhist canons, Pali Tripitaka, Tibetan Tripitaka and the Mahayana texts. Each Buddhist canon is a series of distinct texts. Pali Tripitaka, consists of Vinaya, Sutta and Abhidamma Pitaka. Several sections of the Sutta Pitaka are of high literary value.

The Pali canon was the best preserved, most complete and nearest to the original, said Guruge. The Buddhist texts of the other schools, found in fragments, quotations and translations confirm this. The Vinaya texts of the Sarvastivada School preserved in Chinese and Tibetan translations confirm the antiquity of the Vinaya pitaka.

The rigidity of the Theravada school, the sheltered existence it enjoyed under royal patronage in India and Sri Lanka, the writing down of it in Sri Lanka and the unbroken tradition of learning maintained in monasteries in Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia had helped Theravada to keep the Buddha word in its purity, said Guruge.

The Pali canon also provides information on the Buddha . The oldest version of the life of the Buddha, possibly, is found in the Mahavagga .This is one of the most readable parts of the Canon, too. Digha nikaya provides information which can be used to reconstruct the life of the Buddha, also the contemporary political social and religious history of India. Cullavagga speaks of the First and Second Councils .

Buddhism branched into different schools of Buddhism. But the fundamental doctrines of these different Buddhist schools did not differ. They remained faithful to the original teachings. The core of all these canons is identical. Even the divergences reveal development from a common base. Buddhist texts scattered all over Asia, preserved over time , show common elements. This similarity helps to establish the antiquity and reliability of the contents, observed Guruge.

The Sarvastivada and Mahasanghika schools which had attended the Third Council were the breakaway groups which later developed into Mahayana. By first century Mahasanghika school had its centers in Mathura, India and Afghanistan. The Sarvastivadins were active in Kashmir.

Kushan emperor Kanishka I (120-144) favoured Sarvastivadin School. The Kushan Empire, included Northern India and Afghanistan. Kushan gave royal patronage to Sarvastivadin school. There were many adherents and this was a period of spectacular progress.

Initially, Mahayana and Theravada seem to have run parallel to each other in India. Four philosophical schools of Buddhism arose in India in the 7th century AD. They were Vaibhasika and Sautrantika schools (Theravada) and the Madhyamika and Yogacara schools (Mahayana). These four philosophical schools represented an age of great intellectual activity among the Buddhist of India, said Guruge.

Madhyamika school was funded by Nagarjuna. its centre was Nalanda. Through Nalanda, Madhyamika school exerted enormous influence in Mahayana. Nagarjuna’s chief disciple was Aryadeva. Aryadeva succeeded Nagarjuna as head of the Madhyamika school of thought and also became the head of Nalanda University . Aryadeva was from Sri Lanka . These Madhyamikas were prolific writers . Both Nagarjuna and Aryadeva wrote reams, said Guruge.

The leader of the Yogachara school was Dharmapala. He was succeeded by Silabadhra. Hiuen Tsang studied under Silabadhra at Nalanda. He translated many Yogacara texts to Chinese. There was also Chandragomin, who knew philosophy, medicine, architecture, grammar, and wrote on them. He had lived short periods in Sri Lanka and Tibet.

Silabadhra was followed by Dharmakirti , also a disciple of Dharmapala. Dharmakirthi’s contribution to science of logic was highly regarded and the Yogachara school made a great impact on Buddhist logic, said Guruge. The contribution made by the two Mahayana schools to the development of logic in India was enormous.

the growth of Mahayana was not the result of violent dissensions, disagreements or conflicts as in the case of Christianity. It was gradual. It started with an overlap. both Theravada and Mahayana were accepted in the Kushan empire.

When Hiuen Tsang went to India in 7 AD, he found 54,500 monks who were both Mahayana and Hinayana. There was also another 32000 e Mahayana and 96,000 Hinayana. in Sri Lanka too, the original intention, in my view, was to start with an overlap. That is why Jetavana was placed inside the Mahavihara.

The concept of Buddha hood differed in Mahayana. Mahayana gave Buddha supernatural powers and miracles. There was a pantheon of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, including the five Dhyani Buddhas. Bodhisattvas ranked also most as gods. The most popular bodhisatvas were Avalokitesvara, Manjusri, Vajrapani, and Samantabadra.

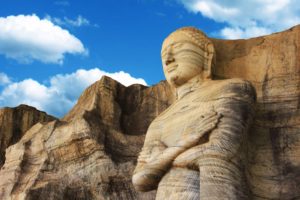

Worship of stupas, Buddha statues , Buddha relics and the Bo tree had begun long before Mahayana. Buddha himself approved the building of Chaitya to enshrine relics. But it is Mahayana that gave supremacy to these external forms of worship. Ceremonies such as taking images and relics in procession became elaborate and popular. This was very different to the simple practices of the early Buddhists who placed greater emphasis on Dana, Sila and Bhavana. But eventually, these Mahayana practices were accepted into the puritanical Theravada as well. There is a great deal of Mahayanism in the Theravada practices in Sri Lanka .

Mahayana used Sanskrit as the medium of communication. There was a substantial Buddhist Sanskrit literature, such as Lalitavistara and many Mahayana writers such as Asvaghosa, (2 cent AD). But most Sanskrit Mahayana texts are in fragments today. Most of the information is taken from Chinese and Tibetan translations.

Mahayana training differed from Theravada. Mahayana included a wide variety of non-Buddhist subjects such as medicine, astronomy, mathematics. Monks were trained also to be disputants. dialectics and logic received utmost attention..

Mahayana set up large institutions, where scholars from various parts of India as well as neighboring countries could attend. The most prominent were Nalanda in Bihar and Valabhi in Gujerat. Chinese monks studies there and recorded their impressions.

Chinese monk Hiuen Tsang ( 602-664)studied for five years at Nalada. His account showed that Nalanda was a fully fledged University with various faculties, admission and examination procedure, libraries and lecture halls. Chinese monk I-Tsing (635-713) studied at Vallabhi for five years. Vallabhi provided training in secular subjects . The course was 2-3 duration, names of exceptional graduates was engraved on gates. The government of Vallabhi recruited Vallabhi graduates for employment.

There was also Vikramasila and Odantapuri, both in present day Bihar and both established in the 8th century . Odantapuri was considered second only to Nalanda. In Vikramasila, admission was gained through participating in a debate. the degree awarded was that of Pandita. these institutions were destroyed by the Muslim rulers arriving in India in the 12 century

Mahayana doctrine was firmly established in China and Tibet. There was a direct route from Gandhara to China. Mahayana went along this route to China. In 5th century AD, Kumarajiva translated Mahayana texts to Chinese. Chinese and Tibetan translations are found even when the original Sanskrit versions of Mahayana doctrine have disappeared.

The third school of Buddhism which rose to importance was that of Tantra or Vajrayana Buddhism. This arose in 8th century AD in Bihar and Bengal. Tantric Buddhism included sex , mysticism, and magical cults. It had prayer wheels, recitations like ‘Om padme hum’ and the Mandala illustration. The central figure was the Buddha Vairocana,. Vajrayana Buddhism became entrenched in Nepal, Tibet , Mongolia and other Himalayan kingdoms.