If there are two classes of goods that dominate the decorative market here in the desert, they would be art glass and studio pottery. Both are midcentury staples and both add shape and color to any decor. Yet while most of our pottery comes from small domestic makers, there are some types with deep roots in other cultures. One of those is celadon, an Asian-based technique that usually (but not always) results in a distinctive pale green glaze. Celadon has a fascinating history and an increasing number of enthusiasts outside the far east. It deserves a visit.

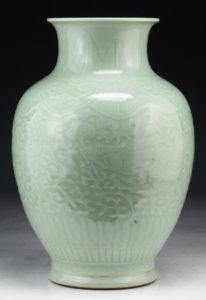

Originated in China centuries ago, celadon pottery in its traditional shade is created when just the right amount of iron oxide is added to the glaze and then fired at high temperature. Too much and the glaze darkens to olive and even black; too little and the glaze turns blue. Neither are necessarily bad outcomes and indeed sometimes reflect the desires of the maker, but celadon’s original green hue and its close resemblance to the color of jade was much of its early attraction. From China, where higher-ups in the imperial court were great enthusiasts, celadon established itself throughout southeast Asia and gained fans in such countries as Japan, Korea and Thailand.

Apart from its green color, celadon glaze is also prone to “crazing,” which is actually a defect but fortuitous in that it leaves the glaze with a distinctive network of fine cracks that doesn’t affect the integrity of the underlying vessel.

This “crackle glaze” adds a patina of age to celadon pottery much in the way that old varnish denotes age in antique oil paintings. Connoisseurs of celadon can not only judge the vintage of an old piece but also its heritage. Chinese celadons have evolved over the centuries in style and color. Those made for export were usually green while certain pieces in brown or off-white were kept for domestic buyers. Designs and ornamentation were kept relatively simple, allowing the glaze to serve as the stand-out feature of the piece.

Japan’s production of celadon followed China’s by some ten centuries. Its adoption was slow — in part due to the high breakage rate of celadon during firing and also because a key ingredient of the glaze was not widely available in Japan.

While some Japanese celedon can be elegant, most was made in utilitarian forms such as sake bowls, cups and plates. Decorative and ceremonial pieces were often fired to produce a blue or bluish-white color. In the last 200 years, a number of prominent Japanese artists have specialized in celadon, some becoming international rock stars among collectors.

Elsewhere, such countries as Korea, Thailand and Vietnam have incorporated celadon into their cultural aesthetics, each with their own unique twists. Korean techniques have evolved steadily over the last thousand years, interrupted only by Mongol invasions during the 13th century. Their pieces are often highly ornamented with layers of clay adding depth and complexity to the forms. Celadon from other regions in southeast Asia is equally distinctive.

Thus, whether by era, color or culture, there are many avenues for celadon collectors to explore and many pieces to be had at very affordable prices. If you’re looking for just the right piece in that distinctive sea-foam green, celadon is a good place to start.

Mike Rivkin and his wife, Linda, are longtime residents of Rancho Mirage.