The Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts in Paris is displaying the fruits of a century of partnership between France and Afghanistan.

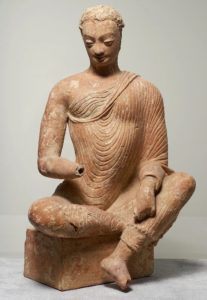

A relaxed Buddha, made of unbaked clay, from around the seventh century, discovered by Jean Carl in 1937 in an excavation by La Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan, or DAFA.

By Nazanin Lankarani

PARIS — Before the Taliban demolished the Great Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001, the figures were the world’s largest standing depictions of the deity. The destruction of the statues, which had stood for 1,500 years, remains one of the most tragic attacks on Afghanistan’s cultural heritage.

With the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, that heritage has become more out of reach. But a new show at the Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts in Paris aims to bring attention to the endangered patrimony of Afghanistan by offering visitors a glimpse of some of its cultural riches. The exhibition marks a 100-year-old partnership with France to unearth and preserve Afghan treasures.

Much of what the rest of the world knows about Afghanistan’s cultural legacy was learned after the end of British influence in 1919. In 1922 a group, La Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (French Archaeological Delegation to Afghanistan), or DAFA, was founded after King Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan invited a French delegation to explore, excavate and help preserve the country’s ancient sites.

Over the next hundred years — except during periods of invasion or war — DAFA worked to uncover artifacts that filled the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul. With the consent of Afghan authorities, duplicates of some of those artifacts, as well as other finds, were donated to the Guimet, where Joseph Hackin, a DAFA director from 1925 until World War II, was its chief curator.

It was during this period that some of the most beautiful pieces were discovered, among them the so-called Bagram ivories, said Nicolas Engel, the museum’s current chief curator and the deputy director of DAFA from 2009 to 2013.

An excavation in Afghanistan, photographed by DAFA’s first director, Alfred Foucher, in 1924.

A selection of such finds, along with paintings and photographs of the country’s heritage sites, are the subject of “Afghanistan, Shadows and Legends,” which opens at the Guimet on Oct. 26 and runs through Feb. 6.

“This museum is intimately connected to the history of the discovery of civilizations of Afghanistan,” Sophie Makariou, president of Guimet, wrote in an email. “Two years ago, together with the National Museum of Afghanistan, we had planned to bring pieces from their collection to Paris. With the fall of Kabul last year, we had to rethink the exhibition.”

A painted mural inside the niche of a Bamiyan Buddha, photographed in 1935. The walls of the niches were painted in the late seventh to early eighth centuries as backdrops for the Buddhas, which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

Mr. Engel said, “Originally we wanted to create a dialogue between the two collections and then show a smaller version of this exhibition in Kabul. But things changed.”

Mohammad Fahim Rahimi, the National Museum’s director in Kabul, did not respond to emails for comment.

Without the artifacts from Kabul’s museum, the exhibition in Paris will still present 375 objects, mostly from DAFA searches and the Guimet’s own collections, with some on loan from the British Museum, the Louvre and France’s National Library.

The show covers a period from the Bronze Age to the 15th century. Bronze Age ceramics, the oldest pieces in the show, are shown alongside miniature paintings, silver plates and a large variety of sculptures in stucco and schist rock.

“A bust from Hadda draped in a Greek-style garment is a good example of the ‘Greco-Buddhist’ style of sculpture found in Afghanistan,” Mr. Engel said. “Paintings from 1935 depicting the niches of the Bamiyan Buddhas reveal their once colorful, painted murals.”

An intricately carved ivory plaque, part of the so-called Bagram ivories discovered by excavators under Joseph Hackin, a DAFA director and Guimet chief curator.

The show also features the Bagram ivories, a rare collection of carved ivory plaques, owned by the Guimet, that were found in Bagram, about 40 miles north of Kabul. The ivories are estimated to date from the 1st or 2nd century.

They were found by DAFA in 1937 and 1939. Mr. Engel said that Mr. Hackin had been searching for a royal city in Bagram when his wife Marie, also known as Ria, stumbled upon two walled-off chambers.

“It is unknown whether the treasure was part of a royal stash or property of a merchant,” Mr. Engel said. “The ivories have Indian iconography; the bronzes and plasters are Roman style; the painted glass are similar to those found in Lebanon.”

The finding, Mr. Engel said, led them to conclude that Bagram had been at the crossroads of long-distance trade routes.

The ivories, as well as some belonging to the National Museum, were presented in a 2007 show at the Guimet titled “Recovered Treasures from Afghanistan” inaugurated by President Jacques Chirac of France and President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan.

About 175 photographs in the upcoming show track a century of exploration in an unfamiliar and challenging land. Some, by the American photographer Steve McCurry, capture the vulnerability of Afghanistan’s heritage sites.

One image from 1992 shows Afghan youths playing at the foot of one of the Bamiyan Buddhas; another from 2003 shows children playing in an abandoned van next to the empty niche where a Buddha, by then destroyed, had stood.

A 1995 photograph shows armed soldiers sheltering inside the National Museum, shortly before the site was looted.

Until the 1950s, France was the only country allowed to excavate in Afghanistan. In 1950, the Afghan government allowed an American delegation to conduct archaeological activity, followed later by Italian, German and Japanese researchers.

Since 1925, the Guimet has regularly exhibited its collection of Afghan artifacts, which Mr. Engel described as some of the “most beautiful archaeological treasures outside of Afghanistan.” But, he added, the more exceptional pieces have remained inside the country, and preservation has been hindered by a lack of funds and international access, as well as poor conservation, as well as deficient conservation, particularly at the Minaret of Jam or the remains of the ancient Buddhist city of Mes Aynak.

“These are real and worrisome emergencies,” Ms. Makariou wrote in the catalog.

Still, Ms. Makariou wrote in an email, “Even if from a distance, we try to advance our understanding of the depths of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage.

“We must keep the flame of research burning.”